Painting conservation techniques can be broken down into support strengthening, cleaning and retouching.

2nd July 2018Painting conservation techniques can be broken down into support strengthening, cleaning and retouching. Within each of these categories a number of different approaches can be seen. The general attitude towards painting conservation is now minimal intervention: the aim of preserving a painting and restoring the visual coherence of the piece somewhat whilst avoiding doing anything that is not necessary. This line of what is and what is not necessary is a real grey area in conservation and can cause controversy.

Differing Attitudes in Painting Support Conservation

The conservation of a painting’s support is often the first step in the restoration process and is fundamental to ensuring that the work in question is stable and can withstand further conservation work. The attitudes towards the conservation of a painting’s support saw significant changes following the Greenwich Conference on Comparative Lining Techniques held at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich in 1974. Westby Percival-Prescott’s keynote address, The Lining Cycle questioned, for the first time, the lining of canvas paintings¹. Up until this point lining had been believed to be a beneficial process and had been carried out extensively². Percival-Prescott suggested that lining might in fact be harmful and unnecessary in many cases, flattening texture and reducing impasto. He suggested the use of minimal heat and pressure and only implementing this on pieces which truly needed lining in order to prevent perceptible deterioration³. This conference was a hugely influential in helping to initiate the current ethos of minimal intervention.

Cimabue, Crucifixion, 1280s, tempera on wood, 3.36 x 2.67 m, Museo di Santa Croce, Florence, after the flood, before restoration, detail. Sourced from Umberto Baldini and Ornella Casazza, The Cimabue Crucifix, (Florence: Olivetti, 1982) p. 104.

Cimabue, Crucifixion, 1280s, tempera on wood, 3.36 x 2.67 m, Museo di Santa Croce, after restoration, details. Sourced from Umberto Baldini and Ornella Casazza, The Cimabue Crucifix, (Florence: Olivetti, 1982) pp. 117 – 118.

However, minimal intervention can be considered to be an ambiguous term. Muñoz-Viñas argues that the term can be considered to be an oxymoron⁴. He uses the analogy of Zeno’s paradox to explain this; just as the arrow would never reach its target, or Achilles would never reach the tortoise due to always being able to devise a lesser distance for Achilles to travel, it is always possible to think of a lesser form of intervention one may have taken⁵.

Cleaning a Painting

The cleaning of a painting is an important part of remedial conservation as it can reveal a painting from a discoloured varnish and can remove previous deceptive restorations, exposing the original paint layers beneath. Cesare Brandi, an extremely influential Italian art historian, argued that one should prioritise the object and its history over the aesthetic image and its removal would need justification⁶. He argues that the painting itself is a historic document and any additions are part of the object’s history⁷. However, many of these additions may not adhere to the original intent of the artist and be applied with a certain level of approximation.

The Delicate Retouching Process

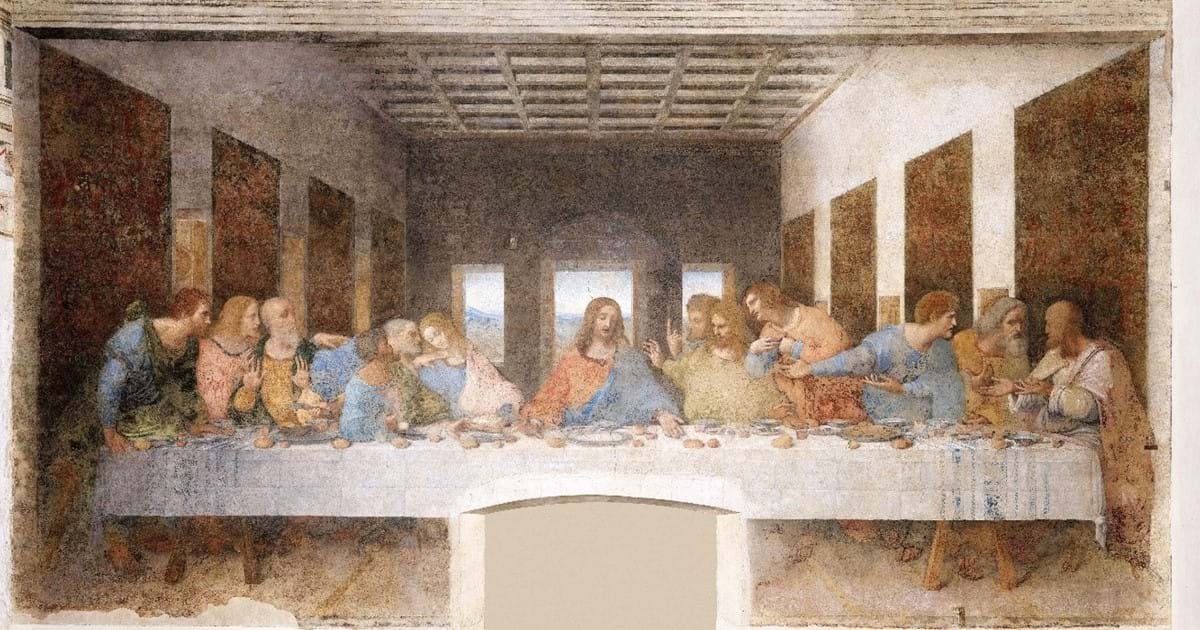

This changing aesthetic through estimated retouchings can be seen in Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. During Pinin Brambilla Barcilon’s recent conservation she removed all previous retouchings, restoring the work to its original paint layers and in the process exposing falsifications that had covered the original and deceived the viewer. Indeed, in this case, in numerous areas repaints covered not only the lacunae but the original paint as well⁸. One such area is the back wall of the composition which was almost entirely repainted⁹. This begs the question, at what point does a work cease being the original and becomes a copy of itself? If the majority of the visible paint has been added in remedial conservation efforts, this suggests that the piece may have become a simulacrum of itself. Therefore, this highlights the importance of cleaning away not only dirty varnishes but also previous retouchings to expose the original.

The retouching stage of painting conservation is hugely significant in the final aesthetic value of a painting. The principal technique used in the UK is deceptive retouching; remedial conservation which seeks to integrate itself in seamlessly into the original, so a complete level of visual unity is kept without distraction. This method is beneficial in providing compositional cohesion and is considered to be ethically sound as long as any additions that are applied can be removed. Reversibility is an overriding priority in conservation practices and is a key principle of minimal intervention.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, c. 1495 - 97/98, tempera and oil on plaster, 4.6 x 8.8 m, Refectory of S. Maria delle Grazie, Milan, the figure of Christ much altered by previous restorations, the same during the cleaning process, the same after the completion of the restoration. Sourced from Brambilla Barcilon, Pinin, and Pietro C. Marani. Leonardo: The Last Supper (Figure 6). (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001) p. 355.

However, if large areas of lacunae are filled with deceptive retouching, if the conservator does not have access to detailed images of the piece before the losses, a certain amount of guesswork must be implemented in filling the lacunae. This is where alternative methods of visible restoration may be more favourable. The Italian method of chromatic abstraction is a technique which builds up hatched brushstrokes of pure colour into a network¹⁰. This technique aims to reduce the visual prominence of the lacunae in a way that does not compete with the original and allows some level of compositional cohesion but does not deny the losses¹¹.

This technique was notably used in the conservation of Cimabue’s Crucifixion. Baldini and Casazza used chromatic abstraction to fill the areas of lacunae. They abstractly incorporated the surrounding colours via the cross-hatching method to reincorporate areas of large loss¹². Chromatic abstraction works on the basis of the human eye blending the colours, as was appropriate to each section, rather than attempting to premix said colours on a pallet before application¹³. This method allows the viewer to read the composition as a whole without applying approximations to areas of loss. However, if the lacunae are vast in size this method can have limitations in the readability of the piece.

Overall, conservation is not a straightforward process in theory or practice. There are a great many areas of disagreement as to the best method of conservation, and the generally favoured methods can be seen to have changed over time. The ethos that a great many conservators adhere to now centre around two main points: minimal intervention and reversibility. The former suggests one should only intervene if necessary for the stability of the piece or to illuminate a previously unreadably painting, but even when action has decided to be taken, only the minimum needed should be actioned. As for reversibility, if additions are to be made, these should be applied in a medium that is removable, therefore making the additions reversible. This makes the conservation more ethical as it is not permanent and can be changed to the state it was in prior to intervention.

[1] Westby Percival-Prescott, 'The Lining Cycle' in Issues in the Conservation of Painting, ed. David Bomford and

Mark Leonard, (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2004). p. 249.

[2] David Bomford, 'The Conservator as Narrator: Changed Perspectives in the Conservation of Paintings' in Personal Viewpoints: Thoughts about Painting Conservation ed. Mark Leonard, (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003). p. 6.

[3] Ibid. p. 264.

[4] Salvador Muñoz-Viñas, “Minimal Intervention Revisited” in Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable

Truths ed. Alison Richmond and Alison Bracker (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2009). p. 49.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Cesare Brandi, Theory of Restoration, ed. Giuseppe Basile, trans. Cynthia Rockwell, (Florence: Nardini Editore,

2005). p. 68.

[7] Ibid. p. 65.

[8] Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, and Pietro C. Marani. Leonardo: the last supper. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001). p. 333.

[9] Ibid. 349.

[10] Kim Muir, Remembering the Past: The Role of Social Memory in the Restoration of Damaged Paintings,

http://www.icom-cc.org/54/document/remembering-the-past-the-role-of-social-memory-in-the-restoration-of-damagedpaintings/?action=Site_Downloads_Downloadfile&id=776,

[Accessed: 05/03/2017].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Baldini and Casazza, The Cimabue Crucifix, (Florence: Olivetti, 1982). p. 16.

[13] Hartman Samet, The Philosophy of Aesthetic Reintegration in Paintings and Painted Furniture, p. 414.